Re-thinking La Russa

For the past week I’ve been wrestling with the nature of Josh Hancock’s death and what role baseball and or the Cardinals played – directly or indirectly – in it. Were they complicit, enablers or just looking out for themselves? I know it’s much too easy to simply blanket the survivors with easy criticisms in such a complicated course of events.

For the past week I’ve been wrestling with the nature of Josh Hancock’s death and what role baseball and or the Cardinals played – directly or indirectly – in it. Were they complicit, enablers or just looking out for themselves? I know it’s much too easy to simply blanket the survivors with easy criticisms in such a complicated course of events.Nevertheless, it’s hard not be critical of Cardinals’ manager Tony La Russa.

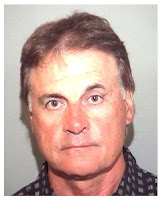

Certainly La Russa has taken a lot of shots in the past week, some have even been fair and thoughtful, while many others seem to be nothing more than piling on. But it is fair to wonder how truly effective a leader of men La Russa can continue to be after Hancock’s death.

Yes, Hancock was an adult and La Russa is not paid to be a babysitter by the Cardinals. In fact, La Russa revealed just today that he had a long discussion with Hancock regarding the pitcher’s drinking as it related to his tardiness three days prior to the fatal accident.

If Hancock would have walked out of the meeting with La Russa and thought to himself, “What a self-righteous hypocrite,” he would have been right. After all, La Russa was busted for DUI on March 22 during spring training. According to the report from the arrest, La Russa was found asleep behind the wheel of his SUV at a traffic light and then struggled to recite the alphabet during a field sobriety test. Currently, La Russa is waiting to go to trial for misdemeanor charges from his arrest.

The Cardinals and MLB are nothing more than pushers of the last legal drug, as alcohol is called by some (and that’s a bigger issue), but La Russa doesn’t set that agenda. His job is to win baseball games and it’s something he does very well. In fact, La Russa seems to have a laser focus on winning games to the point that nothing else matters.

For instance, La Russa has been an ardent defender of Mark McGwire and the allegations of performance-enhancing drug use during the former player’s assault on the single-season home run records. In 2006, after McGwire’s infamous showing before the Congressional House Government Reform Committee, La Russa continued to maintain that his former player was “legal,” which is a bit semantical. McGwire admitted to using then-legal steroid, androstenedione.

“I have long felt, and still do, there are certain players who need to publicize the legal way to get strong,” La Russa told the St. Louis Post-Dispatch in March of 2006. “That’s my biggest complaint. When those players have been asked, they’ve been very defensive or they’ve come out and said ‘Whatever.’ Somebody should explain that you can get big and strong in a legal way. If you’re willing to work hard and be smart about what you ingest, it can be done in a legal way.”

Nothing has dissuaded La Russa from believing McGwire was clean.

“That’s the basis of why I felt so strongly about Mark. I saw him do that for years and years and years. That’s why I believe it. I don’t have anything else to add. Nothing has happened since he made that statement to change my mind.”

La Russa managed the Oakland A’s when McGwire and Jose Canseco were the most-feared slugging duo in the game. Canseco, of course, detailed his (and McGwire’s) steroid use in his book, Juiced: Wild Times, Rampant 'Roids, Smash Hits, and How Baseball Got Big. But when he played for La Russa, Canseco was something of a “steroid evangelist,” as Howard Bryant wrote in his book, Juicing the Game:

La Russa managed the Oakland A’s when McGwire and Jose Canseco were the most-feared slugging duo in the game. Canseco, of course, detailed his (and McGwire’s) steroid use in his book, Juiced: Wild Times, Rampant 'Roids, Smash Hits, and How Baseball Got Big. But when he played for La Russa, Canseco was something of a “steroid evangelist,” as Howard Bryant wrote in his book, Juicing the Game:He talked about steroids all of the time, about what they could do and how they helped him. During the late 1980s and early 1990s, Canseco put the A’s in a difficult position. The question of his steroid use and the possible use by another teammate, budding superstar named Mark McGwire, grew to be an open suspicion.

Deeply compromised was Tony La Russa. Canseco often spoke unapologetically about steroids, yet La Russa did nothing about it. … La Russa knew about Canseco’s steroid use because Canseco had told him so. Under the spirit of baseball’s rules, La Russa could have contacted his boss, Sandy Alderson, who in turn could have told the Commissioner’s office. That’s how the chain of command was supposed to work, but Canseco was a superstar player, an MVP, and the cornerstone of the Oakland revival. Turning him in would have produced a high-profile disaster. La Russa, knowing that his best player was a steroid user, did nothing.

In fact, La Russa did more than nothing. He not only did not talk to Alderson, but actively came to Canseco’s defense. …

But perhaps the best example of La Russa’s unwavering focus on winning baseball games at the sacrifice of everything else came when he was just beginning as Major League manager for the Chicago White Sox in 1983. Just as the White Sox had broken camp and were to begin the ’83 season that ended with the White Sox winning the AL West, La Russa’s wife, Elaine, called from Florida to tell her husband that she and their 4-year old and 1-year old daughters would not be joining him in Chicago because she had, as detailed in Buzz Bissinger’s 3 Nights in August, been diagnosed with pneumonia and required hospitalization.

According to Bissinger:

La Russa responded to the news with a fateful decision, one that would cement his status as a baseball man but would define him in another way.

Based on a strong finish in 1982, the expectations were high for the White Sox in 1983. But the season got off to a wretched start, mired at 16 and 24. Floyd Bannister was having trouble winning anything. La Marr Hoyt had a record of 2 and 6 and Carlton Fisk was a mess at the plate. In the middle of May, the team had lost eight of nine games. Toronto swept them; then Baltimore swept them. La Russa found himself fighting for his life, or what he mistook for his life. He had a team that was supposed to win, that had spent money on free agents and had good pitching and still wasn’t winning. The only reason he was still around was because of the vision of White Sox owner Reinsdorf, who continued to stand by him. So he did what he thought he had to do: He called his sister in Tampa and asked whether she could take care of the kids so he could take care of baseball.

Based on a strong finish in 1982, the expectations were high for the White Sox in 1983. But the season got off to a wretched start, mired at 16 and 24. Floyd Bannister was having trouble winning anything. La Marr Hoyt had a record of 2 and 6 and Carlton Fisk was a mess at the plate. In the middle of May, the team had lost eight of nine games. Toronto swept them; then Baltimore swept them. La Russa found himself fighting for his life, or what he mistook for his life. He had a team that was supposed to win, that had spent money on free agents and had good pitching and still wasn’t winning. The only reason he was still around was because of the vision of White Sox owner Reinsdorf, who continued to stand by him. So he did what he thought he had to do: He called his sister in Tampa and asked whether she could take care of the kids so he could take care of baseball.Bissinger writes that La Russa regretted the decision and has never forgiven himself, but a pattern of behavior that put baseball before anything and everything else was in motion.

I cannot judge whether La Russa could have done anything for Josh Hancock. We are, after all, blessed with free will and the ability to make our own decisions. But it appears very certain that La Russa hasn't done anything different than he had done in the past.

More: La Russa and Cardinals sent wrong message before Hancock's death

Labels: Josh Hancock, Tony La Russa

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home